Nestled on the Qingfeng Plateau in Wen County, Henan province, the village of Chenjiagou seems, at first glance, like countless other rural Chinese settlements. Yet, for over 400 years, this has been the undisputed epicenter and spiritual home of Tai Chi Chuan.

The air itself seems to carry the legacy of a intellectual and martial revolution that began in the 17th century and would eventually captivate the world.

This is the story of Chen-style Tai Chi, a martial art forged in the fires of societal upheaval, refined through generations of a single family, and ultimately recognized as a intangible heritage for all humanity.

It is a narrative not just of fighting techniques, but of philosophical depth, cultural resilience, and an unbroken lineage of masters who dedicated their lives to its preservation and propagation.

The Historical Crucible — From Hongtong to Chenjiagou

To understand Tai Chi, one must first understand the history of Chenjiagou. The village's story begins not with Tai Chi, but with the aftermath of the Yuan Dynasty. Following a period of great turmoil and a government-mandated migration from Hongtong county in Shanxi province in the early Ming Dynasty (1372 AD), a man named Chen Bo settled in the area.

He first established a village named after himself, Chenbu Zhuang. Due to frequent flooding, his family later moved to the higher ground of the Qingfeng Plateau, to a village known as Changyang. Surrounded by ravines on three sides and the Yellow River to the south, this fertile and defensible location became the new home for the Chen clan. As the family flourished and the population grew, Changyang became known by the name it carries today: Chenjiagou, or "Chen Family Ditch."

The Chen family was known for its martial spirit. Chen Bo himself, skilled in boxing and weaponry, established a martial arts school to protect the village from bandits, teaching his descendants and fellow villagers. This tradition of martial practice was passed down through six generations, creating a fertile ground for what was to come.

Chen-style Tai Chi Master Lineage: A Historical Overview

The evolution of Chen Tai Chi can be traced through its most influential masters, each adding a unique chapter to its history.

| Master (Generation) | Era | Key Contributions & Legacy |

|---|---|---|

| Chen Wangting (9th) | 17th Century (Ming/Qing) | The Founder & Synthesizer. A former Ming military commander who, in retirement, created the core system. He blended the Chen family's 108-move Long Fist, 29 postures from General Qi Jiguang's manual, Daoist neidan breathing (from the Huangting Classic), and I Ching philosophy. He created the first five routines of Tai Chi, Pao Chui, Tui Shou (Pushing Hands), and weapon forms, establishing the philosophical and technical foundation for all Tai Chi. |

| Chen Changxing (14th) | 18th-19th Century (Qing) | The Systemizer & Gate-Opener. Codified the scattered family forms into two primary frameworks: the slow, qi-cultivating Yilu (First Routine) and the powerful, explosive Erlu (Pao Chui). Authored seminal theories like "The Ten Essential Theories." His historic decision to break the "family-only" rule and accept Yang Luchan as a disciple marked the first time Tai Chi was taught to an outsider, leading directly to the creation of Yang-style and the art's global spread. |

| Chen Fake (17th) | 20th Century | The Standard-Bearer & "The One and Only." Moved from Chenjiagou to Beijing in 1928, where he famously demonstrated the combat effectiveness of Chen-style Tai Chi in challenge matches, earning the title "Tai Ji Yi Ren" (The One and Only of Tai Chi). His precise "low frame" and powerful demonstrations of Fa Jin became the modern standard. He taught a generation of masters who would propagate the art across the world. |

| Chen Zhaopi (18th) | 20th Century | The Village Guardian. At a time when Tai Chi was dying out in its birthplace, he abandoned a comfortable city life to return to the impoverished Chenjiagou. He established a free school on a threshing ground, single-handedly nurturing the next generation, including the youths who would become the "Four Diamond Kings," thus saving the lineage from local extinction. |

| Chen Zhaokui (18th) | 20th Century | The Technical Conservator. Son of Chen Fake, he was tasked with preserving the technical purity of his father's teachings. He shuttled between Beijing and Chenjiagou, imparting the precise "low frame" and silk-reeling mechanics. He was a fierce defender of the art's authenticity against spurious claims and his demonstrations formed the basis for the first authoritative book on Chen-style Tai Chi. |

| The Four Diamond Kings (19th) | 20th-21st Century | The Global Ambassadors. Comprising Chen Xiaowang, Chen Zhenglei, Wang Xi'an, and Zhu Tiancai, this group was trained under harsh conditions and became the primary force behind the internationalization of Chen-style Tai Chi from the 1980s onward. Through decades of worldwide travel, teaching, writing, and demonstration, they brought the art to over 150 countries, demystifying it for a global audience. |

| Chen Bing (20th) | 21st Century | The Modern Innovator & Bridge-Builder. A national champion and university graduate, he represents the new generation. He founded a global academy, creating structured programs like the "Chen Style Tai Chi Relaxation Qigong" that blend traditional principles with modern sports science and anatomy. He is pivotal in making the profound internal aspects of Tai Chi accessible and relevant to a global, digital-age audience. |

Chen Wangting (1600-1680) — The Founding Sage

The catalyst for Tai Chi's creation was Chen Wangting (1600-1680), a ninth-generation descendant of Chen Bo. Chen Wangting was a man of exceptional talent living in a time of great transition. He was a scholar well-versed in the classics and a formidable martial artist who had served as a county militia commander at the end of the Ming Dynasty.

With the fall of the Ming and the rise of the Qing, Chen Wangting, like many loyalists, found himself without a country to serve. He retreated to his family village, his ambitions unfulfilled. His frustration and refined philosophy are palpable in his poem, "Long and Short Song":

"I recall those years, when I braved the fray, / And swept through hordes of rebels to turn King Ch'ing's sway. / I was oft rewarded, but all in vain; / Now, old and feeble, I have nought to retain. / Only the Huangting Classic stays with me all the time; / When I have leisure, I create boxing; when busy, I farm the land... / Who are the immortals? I am one of their kind!"

In this state of reflective retirement, Chen Wangting embarked on his life's great work. He was not merely creating another fighting style; he was synthesizing a new system based on a unified theory of the universe. He drew upon three primary sources:

- Existing Martial Arts: He studied his family's 108-move Long Fist style and, crucially, incorporated 29 of the 32 postures from the renowned anti-pirate general Qi Jiguang's military training manual, Jixiao Xinshu (New Treatise on Military Efficiency).

- Daoist Philosophy and Practices: He integrated the principles of Yin and Yang from the I Ching (Book of Changes) and Daoist neidan (internal alchemy) practices, including daoyin (guiding energy) and tunagu (breathing exercises).

- Traditional Chinese Medicine: He wove in concepts of meridians and qi (vital energy) circulation from Chinese medical theory.

From this fusion, Chen Wangting created a revolutionary martial art. His system included:

- Five routines of empty-hand Tai Chi.

- One routine of Pao Chui (Cannon Fist).

- The practice of Tui Shou (Pushing Hands), a two-person training method for developing sensitivity, balance, and martial application without causing serious injury.

- Weapon forms, including saber, spear, sword, staff, and a unique "sticky spear" practice.

This was the birth of Chen-style Tai Chi—a system that embodied dynamic contrast, where slow, soft movements seamlessly transitioned into fast, powerful explosions, all guided by the spiraling energy of Chan Si Jin (Silk Reeling Energy).

The Architects of Modern Chen Style

For over a century, Tai Chi remained a closely guarded secret within the Chen family. Its transformation into a global art began with two key figures in the 18th and 19th centuries.

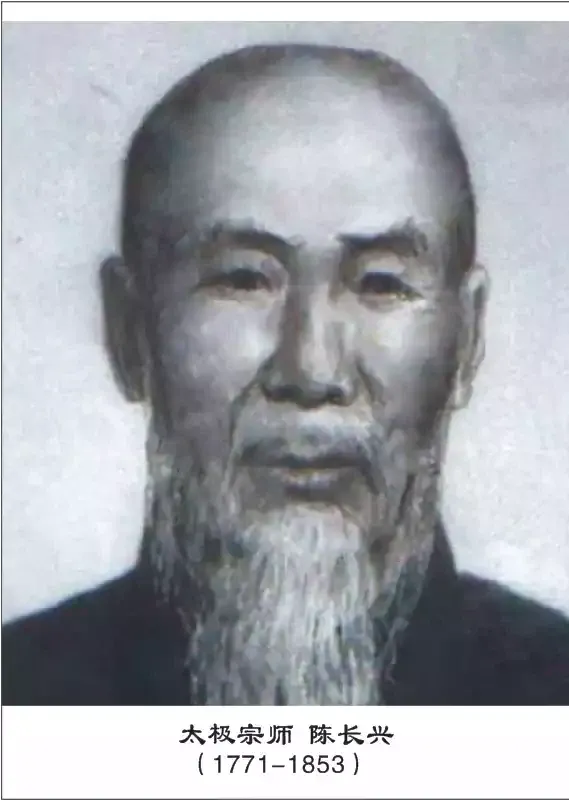

Chen Changxing (1771-1853) — The Systemizer and Gate-Opener

As a 14th-generation master, Chen Changxing, known as "Mr. Tablet" for his impeccable posture, recognized the need to standardize the family art. He distilled the various forms into two primary, codified routines: **

- Yilu (First Routine): A slower, more internal form focusing on cultivating qi, correct body alignment, and the fundamentals of Chan Si Jin.

- Erlu (Second Routine, Pao Chui): A fast, powerful, and explosive form demonstrating the martial application of the energy developed in Yilu.

His theoretical works, "The Ten Essential Theories of Tai Chi" and "The Martial Words of Tai Chi," provided a comprehensive philosophical and practical framework for the art.

Chen Changxing's most revolutionary act was breaking the clan's tradition of "passing only to male family members." He accepted an outsider, Yang Luchan, as a live-in disciple.

Yang, a determined servant from Hebei province, learned the art and later founded his own style, Yang-style Tai Chi, which would become the world's most popular and widely recognized form.

This single act of openness ensured Tai Chi would not remain a village secret but would become a national treasure.

Chen Youben & Chen Qingping — The Refiners of the "Small Frame"

While Chen Changxing was standardizing what became known as the "Big Frame" (Da Jia), his contemporary Chen Youben (1780-1858) was refining a more compact, subtle version known as the "Small Frame" (Xiao Jia). This framework was characterized by smaller, tighter circles and intricate internal movements.

His student, Chen Qingping (1795-1868), further developed this Small Frame after moving to Zhaobao town. His teachings became known as the Zhaobao Frame and were instrumental in the development of other major Tai Chi styles, such as Wu (Hao) style.

The Standard-Bearers — Theory and Practice in the 20th Century

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw Chen Tai Chi face new challenges and opportunities as China modernized. Two masters, one of theory and one of practice, ensured its survival and relevance.

Chen Xin (1849-1929) — The Grand Theorist

A 16th-generation master, Chen Xin undertook a monumental task. Fearing the oral tradition might be lost, he spent the final twelve years of his life writing Chenshi Taijiquan Tushuo (Illustrated Explanation of Chen Family Tai Chi). This multi-volume work is the most comprehensive classical text on Tai Chi. It uses the I Ching, Yin-Yang theory, and Chinese medical science to explain every movement and its relationship to Chan Si Jin and internal energy cultivation. He established the complete theoretical system that Chen-style Tai Chi rests upon today.

Chen Fake (1887-1957) — The "One and Only"

The grandson of Chen Changxing, Chen Fake is a towering figure in modern Chen Tai Chi history. In 1928, he traveled to Beijing, where the perception of Tai Chi was dominated by the soft, graceful Yang style. Many in the capital dismissed the Chen style as crude "country boxing."

Chen Fake responded by accepting all challenges. His demonstrations of Chan Si Jin and explosive Fa Jin (issuing power) were breathtaking. He effortlessly defeated challengers from various martial arts, earning the deep respect of the Beijing martial community. They presented him with a golden shield inscribed with the characters: "Tai Ji Yi Ren" — "The One and Only of Tai Chi."

For nearly 30 years, he taught in Beijing, and his version of the forms, characterized by low stances, clear silk-reeling motions, and powerful fa jin, became the modern standard for Chen style. He taught a generation of masters who would spread the art across China and beyond, cementing his reputation as the foremost practical master of his era.

The Guardians — Preserving the Flame in Modern Times

The mid-20th century, with its wars and social upheaval, posed an existential threat to Tai Chi in its birthplace. The survival of the art in Chenjiagou is owed to the heroic efforts of two 18th-generation masters.

Chen Zhaopi (1893-1972) had established a reputation teaching in Nanjing. Upon hearing that the practice had nearly died out in Chenjiagou, with young people dispersed and disinterested, he gave up his comfortable life and returned to the impoverished village. He turned a threshing ground into a makeshift school, teaching for free and even using his own pension to incentivize learning. His unwavering dedication nurtured the next generation—a group of young boys who would become known as the "Four Diamond Kings of Chenjiagou."

Chen Zhaokui (1928-1981), the son of Chen Fake, was tasked with preserving the technical purity of the art. He traveled between Beijing and Chenjiagou, imparting his father's precise "low frame" teachings. A highly educated man, he meticulously recorded techniques and theories, creating invaluable written records. He also fiercely defended the authenticity of his family's transmission against claims of "new" versus "old" frames, insisting on the unity and integrity of the lineage.

The Global Diaspora and a New Era of Recognition

The "Four Diamond Kings" — Chen Xiaowang, Chen Zhenglei, Wang Xi'an, and Zhu Tiancai —, trained in the harshest conditions, became the standard-bearers for Chen Tai Chi's global spread from the 1980s onward.

They traveled relentlessly to over 150 countries, authoring books, producing videos, and establishing schools that demystified the art for a worldwide audience.

This global journey reached a symbolic peak on December 17, 2020, when UNESCO's Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage inscribed "Taijiquan" onto its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

This formal recognition affirmed Tai Chi not merely as a sport or exercise, but as a profound cultural practice embodying traditional Chinese philosophy, health maintenance, and community cohesion.

The tradition of recognizing masters continues at the national level. On March 17, 2025, China's Ministry of Culture and Tourism announced the sixth group of National Representative Inheritors of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

The list for Taijiquan included seven masters, among them Chen Peiju (Chen-style), Chen Xiaoxing (Chen-style), and Chen Bing (Chen-style), signifying the ongoing, vibrant transmission of the art into the 21st century.

Today, a new generation like Chen Bing (20th Generation) embodies the future. A national champion with a university degree, he bridges tradition and modern science.

He founded a global Tai Chi academy, creating teaching methods that make the profound principles of Chan Si Jin and Qi accessible to a global, digital audience. His work ensures that the art remains a living, evolving practice, not a museum relic.

Epilogue: The Unbroken Circle

From the creative genius of Chen Wangting to the global classrooms of masters like Chen Bing, the story of Chen-style Tai Chi is one of remarkable continuity and adaptation. It is a story of a family, a village, and a philosophy that learned to breathe with the times.

In Chenjiagou today, the past and present coexist. The morning mist still rises over the same fields where Chen Wangting once trained, but now the sounds of practice include the voices of students from every corner of the globe.

They come to touch the source, to learn the movements that contain within them centuries of wisdom, resilience, and a simple, powerful truth: that softness can overcome hardness, that yielding can be a form of strength, and that in the balance of Yin and Yang, we can all find our center in a rapidly spinning world.

Demystifying Chen Style Tai Chi 56 Form: A Complete Guide to the Spiral-Powered Practice

Frequently Asked Questions About Tai Chi Masters

Who was the first Tai Chi master?

While legend exists, historical records point to Chen Wangting (1600-1680) as the foundational Tai Chi master. He synthesized the art in Chenjiagou village during the Ming-Qing transition, drawing from existing martial arts, Daoist philosophy, and traditional medicine.

What makes a Chen-style Tai Chi master different?

A true Chen-style Tai Chi master is not just a skilled practitioner but a lineage holder. They possess deep knowledge of the core components that define the style: the dynamic interplay of slow (Yilu) and fast (Pao Chui) movements, the application of explosive Fa Jin power, and the mastery of the foundational Chan Si Jin (Silk Reeling Energy) that runs through all techniques.

Who was the Tai Chi master known as "The One and Only"?

This title was bestowed upon Master Chen Fake (1887-1957) by the Beijing martial arts community in the early 20th century. After moving from Chenjiagou to Beijing, he demonstrated the unparalleled combat effectiveness of Chen-style Tai Chi through a series of challenge matches, single-handedly establishing its credibility and power in the capital.

How did the Tai Chi master Chen Changxing change history?

Master Chen Changxing (1771-1853) was pivotal in two ways. First, he systematized the family's art into the standardized "Old Frame" routines still practiced today. Second, and most importantly, he broke the "family-only" transmission rule and accepted the outsider Yang Luchan as a disciple. This act allowed Tai Chi to spread beyond Chenjiagou, leading to the creation of Yang-style and all subsequent major styles.

Are there official recognitions for modern Tai Chi masters?

Yes. In addition to global recognition like the 2020 UNESCO inscription, national governments formally honor masters. For instance, in March 2025, China's Ministry of Culture and Tourism named several individuals, including Chen Bing, Chen Peiju, and Chen Xiaoxing, as National Intangible Cultural Heritage Inheritors, officially recognizing their status as key bearers of the Tai Chi master legacy.

What is the significance of Chenjiagou for a Tai Chi master?

Chenjiagou is the holy ground and birthplace of Tai Chi. For any serious Tai Chi master or practitioner, it is a place of pilgrimage. It is the source of the original art, home to the ancestral hall of the Chen family, and a living museum where the authentic lineage has been preserved and passed down for over 400 years.

Who are the "Four Diamond Kings" of Tai Chi?

They are four renowned 19th-generation Chen-style Tai Chi masters: Chen Xiaowang, Chen Zhenglei, Wang Xi'an, and Zhu Tiancai. Trained during difficult times, they became the primary ambassadors who globalized Chen-style Tai Chi from the 1980s onward, teaching tens of thousands of students worldwide and solidifying their status as modern-era master legends.