You’ve probably seen it in movies. A whirlwind of kicks soaring through the air. A flurry of precise, close-range punches. But have you ever wondered why Chinese martial arts seem to split so dramatically into these two styles?

Welcome to the world of "Nan Quan Bei Tui" – Southern Fist, Northern Leg.

This isn't just a cool saying; it's the fundamental geographic and philosophical divide that shaped Kung Fu for a thousand years. It’s a story written not just in history books, but in the very bodies and landscapes of China.

At Tai Chi Wuji, we see this as a perfect example of how environment shapes art, and how opposing forces—like Yin and Yang—create a beautiful, powerful whole.

So, let's journey back to where it all began. How did this legendary split start?

Where the Divide Began: A Kung Fu Origin Story

Every great art needs an origin story. For Southern Fist and Northern Leg, ours begins in the chaos and creativity of ancient China.

The Song Dynasty: A Legendary Kung Fu Summit

Picture this: It's the early Song Dynasty (around 960 AD). China is reunifying. And in the city of Changsha, a massive, national martial arts tournament is held.

This is where legend and history shake hands.

On one side, you have the "Tai Zu Quan" or Emperor's Long Fist, developed by the founding Emperor himself, Zhao Kuangyin. Hailing from south of the Yellow River, his style was a precursor to what we now call Southern Fist. It focused on powerful, stable stances and close-range power.

On the other side, from north of the Yellow River, was "Tan Tui" or "Springing Leg." Its creator? The mysterious Kunlun Master, who folklore says was actually a defeated general named Li Zhongjin. After a failed rebellion, he supposedly retreated to Longtan Temple in Shandong and created this revolutionary leg-oriented style.

At that tournament, the story goes, Emperor Taizu's fist took first place, and Kunlun's legs took second. And just like that, the phrase "Southern Fist, Northern Leg" was born.

- But is it true? The Ming Dynasty military text Wubei Zhi confirms the high status of these styles, listing them among the "18 Schools of Song Martial Arts." It states: "Song Taizu Long Fist is the first of the 18, Linqing Tan Tui is the most revered."

- The Tai Chi Wuji Perspective: We love this story because it highlights a core principle we teach: the blend of structure (the historical record) and flow (the legend). The idea of this contest, whether every detail is factual or not, gave generations of martial artists a cultural touchstone. It created a shared identity. This is how tradition is built.

The Grand Canal: Kung Fu’s Ancient Superhighway

But how did these styles spread? For Northern Leg, the answer is literal water under the bridge.

The Grand Canal, one of history's greatest engineering feats, was the internet of its day. It moved goods, people, and ideas.

The Northern Route

The Linqing Tan Tui style, born at the Longtan Temple (which, after a 1964 border adjustment, is now in Hebei province), used this watery highway. Practitioners and disciples traveled the canal, spreading the art.

- Proof? Archaeological finds near the temple—ancient docks, even old leg-training equipment—back up the historical records.

- This is how Tan Tui reached the Shaolin Temple and evolved into the famous Shaolin Twelve-Road Tan Tui, and how it influenced the Muslim community to create Jiaomen Tan Tui.

The Southern Route

Southern Fist, like the powerful Hung Kuen, spread differently. It moved south from Fujian's Southern Shaolin Temple, carried by merchants and migrants along the river networks of the Pearl River Delta. It was the "Lingnan merchant gangs" who helped it take root in Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hainan.

The bottom line? Geography is destiny. The map of China didn't just shape its borders; it shaped its fighting styles. Northern legs traveled by canal; southern fists moved with the coastal trade.

In our next section, we'll break down the actual science of these styles. Why exactly are southerners known for their fists, and northerners for their legs? The answers might surprise you.

The Science of Style: It’s All About Adaptation

So, we have our history. But let's get practical. What does "Southern Fist, Northern Leg" actually feel and look like? And more importantly, why did these styles evolve so differently?

It all comes down to brilliant, centuries-long adaptation. Let's break down the key differences.

A Tale of Two Bodies: The Biomechanics of Kung Fu

Think of it like this: Southern Fist is a compact sports car, built for tight corners and quick acceleration. Northern Leg is a powerful off-road vehicle, built for open terrain and high-speed cruising.

Here’s a quick comparison:

| Dimension | Southern Fist (e.g., Hung Kuen, Wing Chun) | Northern Leg (e.g., Linqing Tan Tui, Shaoli Tan Tui) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Technique | Close-range punches, infighting, "inch power" (Cun Jin) | Long-range kicks, sweeping movements, "releasing long" |

| Body Posture | Low, stable stances ("Hard Bridge, Hard Horse") | Higher, mobile stances ("Steps follow the body's turn") |

| Power Generation | Short-distance explosion using tendon strength and torque | Long-distance power using the waist to whip the legs |

- Southern Fist's "Inch Power" (Cun Jin): This isn't just muscle. It's a biomechanical marvel. Imagine generating a shocking amount of force in just a few inches. This is done by coordinating the joints—shoulder, elbow, wrist—in a rapid, sequential snap. Some theories suggest this efficiency was perfect for the generally compact builds of southern Chinese populations, maximizing their fast-twitch muscle fibers.

- Northern Leg's "Power Kicking": This is all about leverage. Longer limbs, more common in the taller northern populations, act as natural levers. By engaging the core and waist, a practitioner can generate tremendous force, like cracking a whip. The power doesn't start in the foot; it starts in the ground, travels up the leg, and is unleashed by the hip.

Beyond the Obvious: The Hidden Reasons for the Split

Sure, geography and body type matter. But the real, gritty reasons are found on the ancient battlefield and in the fields.

Military Needs Shaped Technique

- In the NORTH: The frontier was a constant battlefield against nomadic cavalry. How do you fight a man on a horse? You need long-range, powerful techniques to unseat him. Legs were the ultimate cavalry deterrent. Kicks could target the horse or the rider from a safer distance.

- In the SOUTH: The landscape was hills, rice paddies, and dense villages. Warfare was often guerrilla tactics or cramped street fights. Here, wide swings and high kicks were a liability. You needed short, fast, powerful punches and elbow strikes that worked in a phone booth.

Daily Life Built the Body

- Northerners often engaged in vast-field farming, which meant long walks, carrying heavy loads, and deep squats. This built incredible lower-body strength and endurance—the perfect foundation for a kicking art.

- Southerners were often involved in rice cultivation (bent-over postures), fishing, and intricate crafts like weaving. This developed tremendous upper-body dexterity, strong hands, and a lower center of gravity—the perfect recipe for powerful fist techniques.

Here at Tai Chi Wuji, we find this fascinating. It shows that Kung Fu wasn't invented in a vacuum. It was a logical, intelligent response to the world around it. The environment, the threats, the daily work—all of it got coded into the muscle memory of an entire culture. It's a powerful reminder that the most effective systems are those that adapt to reality, not fight against it.

Coming up, we'll meet the iconic masters and styles that kept this incredible heritage alive. Get ready for heroes like Wong Fei-Hung, Ip Man, and the guardians of the legendary Tan Tui.

The Heroes and Their Legacies: Masters of Fist and Leg

History and science are cool, but let's get to the good stuff: the people. The masters who turned principles into powerful, living traditions. These aren't just names in a book; they're the reason we can still learn Southern Fist and Northern Leg today.

Who were these legendary figures, and what made their styles so special?

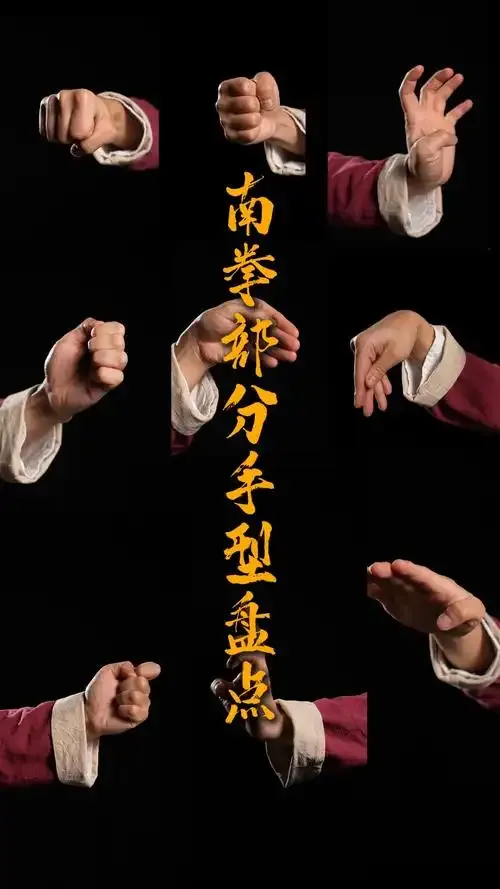

Southern Fist: The Art of Short-Range Power

Southern styles are like a fortress. They are stable, powerful, and devastating up close. Let's meet the big three.

Hung Kuen: The Unshakable Foundation

If Southern Fist had a king, it might be Hung Kuen. Known for its "Hard Bridge, Hard Horse" philosophy, this style is all about rooted stances and powerful, straightforward attacks.

- What makes it unique? It’s built for overwhelming an opponent. Practitioners train their arms to be like iron ("bridge" refers to the forearm), and their stances to be as immovable as a mountain. Its most famous set, Tit Sin Kuen (Iron Wire Fist), is a masterpiece of internal power and tendon strengthening.

The Masters:

- Hung Hei-gun: The legendary founder, a student of the Southern Shaolin Temple. He's the embodiment of anti-Qing rebellion and raw power.

- Wong Fei-hung: Perhaps the most famous Chinese folk hero. A physician, martial artist, and moral leader. His mythos, including the "No Shadow Kick," made Hung Kuen a symbol of righteousness. He's a perfect example of the Tai Chi Wuji ideal: a warrior who was also a healer.

Wing Chun: The Science of Efficiency

Now, let's talk about the style that took over the world. Wing Chun is the brainy, efficient counterpart to Hung Kuen's brute force. It’s physics applied to fighting.

- What makes it unique? Its core principle is the Centerline Theory. Attack and defend the central line of the body—the shortest path. It uses sensitivity drills like Chi Sao (Sticky Hands) to develop lightning-fast reflexes. It’s not about being stronger; it's about being smarter and faster.

The Masters:

- Ip Man: The grandmaster who brought Wing Chun out of secrecy and into the public light in Hong Kong. His discipline and refined teaching methods created a generation of legends.

- Bruce Lee: Ip Man's most famous student. He took Wing Chun's principles of directness and efficiency and used them as the foundation for his own art, Jeet Kune Do. He's the ultimate symbol of adaptation—taking tradition and making it modern.

Choy Li Fut: The Complete Hybrid

Want the best of both worlds? Choy Li Fut might be it. It uniquely blends the short-range power of Southern Fist with the long, sweeping, circular movements often seen in northern styles.

- What makes it unique? It's one of the few southern styles that extensively uses both hands and feet. It’s powerful, fluid, and incredibly versatile. This style shows that the "Southern Fist, Northern Leg" divide wasn't a rigid wall, but a spectrum.

The Master:

- Chen Xiang: The founder who brilliantly combined the techniques of three different masters into one cohesive, powerful system.

Northern Leg: The Art of "Reaching Out"

Now, let's head north, where the philosophy is "Hands are like two doors, everything depends on the legs to kick the man."

Linqing Tan Tui: The Root of All Northern Legs

This is the source. Tan Tui, or "Springing Leg," is the bedrock. Its name is legendary, and its practice is foundational for many northern styles.

- What makes it unique? The core is the "Ten Roads of Tan Tui." These routines are drilled relentlessly to build power, stability, and coordination. A key principle is "Tan Tui does not kick above the knee," focusing on low, devastating kicks to break an opponent's structure. It's pragmatic and powerful.

The Masters:

- The Kunlun Master: The mythical founder, whose story we already love. He represents the ingenuity of creating a leg-dominant system.

- Modern Guardians: Today, masters like Li Zhengguo are ensuring its survival, getting Tan Tui into the school curriculum in its hometown region. This is how a 1,000-year-old art stays alive.

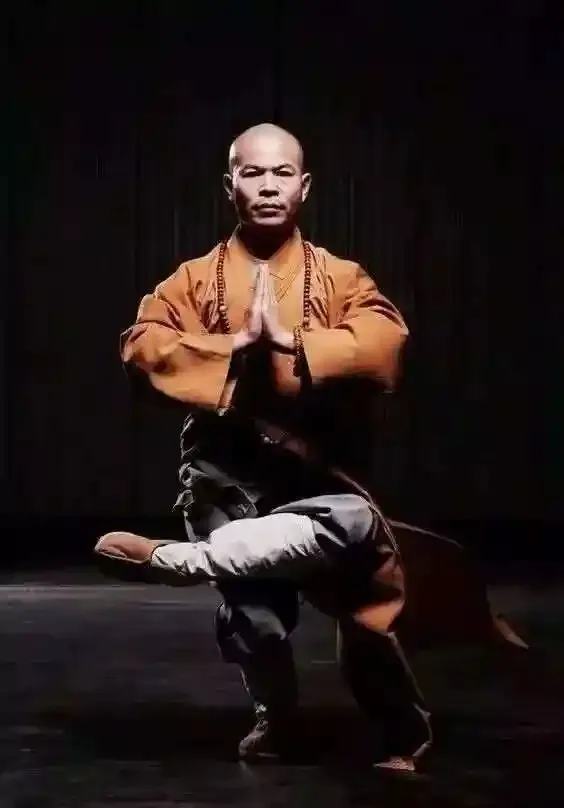

Shaolin Tan Tui: The Monastery's Foundation

When Tan Tui traveled up the canal to the Shaolin Temple, the monks made it their own. They added two more roads, creating the Twelve Roads of Shaolin Tan Tui.

- What makes it unique? This is often the very first thing a Shaolin student learns. It builds the leg strength, endurance, and fighting intuition for all the more complex Shaolin forms that follow. If you've ever seen a Shaolin demo with blindingly fast, continuous kicks, you've seen Tan Tui's influence.

Chuo Jiao: The "Poking Foot" Specialist

If Tan Tui is the foundation, Chuo Jiao is the precision striker. Its name means "Poking Foot," and it specializes in swift, pinpoint kicks with the toe.

- What makes it unique? It's fierce and direct. Chuo Jiao is less about sweeping power and more about attacking vital points with terrifying accuracy. It’s a living example of the incredible technical diversity within the "Northern Leg" umbrella.

So, we have these incredible living traditions. But here's the big question we get at Tai Chi Wuji all the time: Is this ancient stuff still relevant in the modern world? The answer is a resounding YES.

Let's see how.

From Ancient Temples to the Global Stage: Your Kung Fu is Alive

It's easy to think of this as a museum piece. But that's a huge mistake. Southern Fist and Northern Leg are more alive than ever. They've just found new arenas.

How are these ancient arts thriving in the 21st century?

The Netflix Effect: How Pop Culture Became a Kung Fu Master

Let's be real. Movies and TV have done more for Kung Fu in the last 20 years than anything else.

- The Ip Man Series: These films didn't just make Wing Chun popular; they made it desirable. They showed the philosophy, the discipline, and the sheer coolness of a southern style.

- The Shaolin Temple: The classic 1982 Jet Li movie put Shaolin Kung Fu—and its foundational Tan Tui—on the global map.

What this means: Pop culture creates a gateway. It sparks curiosity. At Tai Chi Wuji, we see new students walk in all the time saying, "I saw this in a movie, and I had to try it." That initial spark is priceless.

The Gymnasium and The Dojo: Modern Training Grounds

Forget just secret lineages. Kung Fu has entered the mainstream in a big way.

- Public Schools: As we mentioned, Tan Tui is part of the PE class in parts of Hebei. In Foshan, the hometown of Ip Man, tens of thousands of schoolkids are learning Wing Chun. This isn't just preservation; it's giving kids a connection to their culture and a great workout.

- Sport & Competition: Look at the Wushu competitive scene. There are separate, prestigious competitions for Nan Quan (Southern Fist) and routines that feature classic northern leg techniques. This pushes the arts to new levels of athleticism and perfection.

The MMA Connection: This is the big one.

Skeptics ask, "Can this old stuff work in a real fight?" Modern Mixed Martial Arts has provided the answer. While few fighters use a "pure" traditional style, the principles are everywhere.

- The close-range, rapid punches of Wing Chun? See them in the boxing-infused infighting of a UFC champion.

- The powerful, roundhouse kicks of northern styles? They're a standard weapon in every MMA fighter's arsenal.

Bruce Lee was decades ahead of his time. He saw that the future was in breaking down the barriers between styles. His Jeet Kune Do was the ultimate fusion of Southern Fist's efficiency and Northern Leg's reach.

So, the journey isn't over. It's just entering a new, exciting phase. In our final section, we'll bring it all together and ask the most important question: What does all this mean for you?

The Fusion Force: What "Southern Fist, Northern Leg" Teaches Us Today

So, we've journeyed from legendary tournaments to biomechanics, and from iconic masters to movie screens. Now, let's land in the present. In our modern, connected world, does the old divide between Southern Fist and Northern Leg even matter anymore?

The answer is fascinating: The divide is less a border and more a conversation. And that conversation is creating the most exciting chapter in Kung Fu's history.

No More Walls: The Beautiful Blending of Kung Fu

Think about it. We are no longer limited by the village we were born in. A kid in Ohio can watch a Wing Chun tutorial online and then go to a class to learn Muay Thai kicks. This global exchange has shattered old geographic limits.

The Ultimate Example: Bruce Lee's Jeet Kune Do. Bruce was the prophet of this fusion. He took the close-range, efficient punching of Southern Fist (Wing Chun) and fused it with the long-range, powerful kicking of Northern Leg (like the side kick). He didn't see "Southern" or "Northern"; he saw "useful" and "efficient."

The Modern Standard: Sanda (Sanshou). This is the official Chinese modern combat sport. And what is it? It's the living proof of this fusion. A Sanda fighter uses:

- Southern Fist-style punches for close combinations.

- Northern Leg-style kicks (like the powerful sweep kick) to control distance and score points.

- They even add throws and takedowns!

Sanda is the ultimate expression of "take the best, discard the rest." It’s the scientific, modern child of the Southern Fist and Northern Leg legacy.

At Tai Chi Wuji, this is the philosophy we embrace. We respect the deep roots and traditional forms, but we also understand that for a art to be alive, it must breathe and adapt. The true "secret" of Kung Fu isn't a hidden technique; it's the principle of adaptive efficiency.

The Real "Secret" of Southern Fist and Northern Leg

Forget the magic bullet. After a thousand years of evolution, the real lesson isn't about choosing fists over legs. It's about understanding the context for each.

- The Southern Fist Lesson: How to be powerful, rooted, and devastating in a confined space. It’s the wisdom of making a little go a long way. It teaches you to be an unmovable rock.

- The Northern Leg Lesson: How to use space, leverage, and your longest weapons to control the fight. It’s the wisdom of expansive power and strategic distance. It teaches you to be an unstoppable wave.

This is the Yin and Yang of Chinese martial arts. One is not better than the other. They are complementary forces. A complete martial artist isn't just a "fist" person or a "leg" person. They are a movement person. They know when to be compact and when to be expansive.

This is why at our school, we encourage cross-training. Understanding the principles of Wing Chun can make your Tan Tui more intelligent. Understanding the power of Tan Tui can give your Wing Chun a new dimension.

Your Kung Fu Journey Awaits

So, where does this leave us? The story of Southern Fist, Northern Leg is far from over. It's simply being rewritten by a global community.

It’s being written by:

- The Sanda athlete drilling combinations.

- The Wing Chun student practicing "sticky hands."

- The fitness enthusiast adding Tan Tui lines to build leg strength.

- The curious kid watching Ip Man for the first time.

This thousand-year-old conversation between the fist and the leg is now an invitation—to you.

You don't have to choose a side. The real power lies in understanding both. It’s about finding your own balance between structure and flow, between power and precision, between the unmovable rock and the unstoppable wave.

This is the journey of a lifetime. And it starts with a single step—or a single punch.

What's your style? Discover the balance at Tai Chi Wuji.

FAQ

What is the simple definition of "Southern Fist, Northern Leg" (Nan Quan Bei Tui)?

"Southern Fist, Northern Leg" is a classic Chinese saying that summarizes the core geographic split in Kung Fu styles. It means southern Chinese martial arts (like Wing Chun and Hung Kuen) famously emphasize powerful, short-range fist techniques and stable stances, while northern styles (like Tan Tui and Chuo Jiao) are renowned for their dynamic, long-range kicking techniques and agile footwork.

What is the main difference between Southern and Northern Kung Fu styles?

The main difference lies in their core fighting philosophy and biomechanics: Southern Styles (Fist): Focus on close-quarters combat, low stances (like the horse stance), and generating short-power bursts (Cun Jin/寸劲). Think compact and powerful. Northern Styles (Leg): Prioritize long-range engagement, use high, mobile stances, and generate power through whipping kicks and sweeping movements. Think expansive and agile.

Why did this "Southern Fist, Northern Leg" difference develop?

The divergence wasn't random; it was a brilliant adaptation to environment and history: Geography & Climate: Southern China's hills and rivers favored close-range combat, while the northern plains allowed for wide, kicking maneuvers. Body Types: Historically, northern populations were often taller with longer limbs, ideal for kicking. Southerners often had more compact builds, perfect for generating powerful, short-range force. Military History: Northerners fought cavalry, where long legs were key to unhorse riders. Southerners engaged in infantry and guerrilla warfare in tight spaces, where fist and elbow strikes were more effective.

Is Wing Chun a "Southern Fist" style?

Absolutely. Wing Chun is a quintessential Southern Fist style. It perfectly embodies the southern principles with its focus on the centerline theory, close-range infighting, short-power punches (like the chain punch), and sensitivity training through Chi Sao (Sticky Hands).

What is Tan Tui, and why is it so important for Northern Leg styles?

Tan Tui (Springing Leg) is one of the most foundational Northern Leg systems. Its "Ten Roads" (or twelve in Shaolin) are drilling routines used for centuries to build the leg strength, stability, and coordination essential for all northern kicking techniques. Many northern styles, including Shaolin Kung Fu, require students to master Tan Tui first.

Are there any styles that mix both Southern Fist and Northern Leg?

Yes! This fusion is a key trend in modern martial arts. The most famous historical example is Choy Li Fut, a southern style that incorporates long, sweeping northern-style arm and leg techniques. In modern times, Bruce Lee's Jeet Kune Do was built on this fusion, and the Chinese combat sport Sanda (Sanshou) explicitly combines Southern-style punches with Northern-style kicks and throws.

Which is more effective for self-defense: Southern Fist or Northern Leg?

Effectiveness depends on context. Southern Fist styles like Wing Chun are highly effective in confined, close-range situations (e.g., a hallway or elevator). Northern Leg styles offer superior control of distance and power in open spaces. A modern self-defense approach, much like what we advocate at Tai Chi Wuji, involves understanding the principles of both to be adaptable.

As a beginner, should I start with a Southern or a Northern style?

It depends on your goals and physique: Start with a Southern style (like Wing Chun) if you are interested in close-range combat, developing sensitivity and reflexes, and prefer a style that doesn't rely heavily on flexibility. Start with a Northern style (like foundational Tan Tui) if you want to improve your flexibility, athleticism, and kicking power, and enjoy dynamic, acrobatic movements. The best choice is a school that understands both traditions and focuses on solid fundamentals.

How can I see authentic Southern Fist and Northern Leg Kung Fu today?+

You can experience them through: Traditional Kung Fu Schools: Look for schools specializing in specific lineages like Hung Kuen, Wing Chun, Tan Tui, or Shaolin Kung Fu. Modern Competitions: Watch Wushu tournaments, which have separate Nan Quan (Southern Fist) and Chang Quan (Long Fist, which includes northern techniques) events. Cultural Heritage Sites: Visit places like Foshan (the heart of Wing Chun) or the Shaolin Temple to see the living culture.

How does Tai Chi Wuji incorporate the principles of Southern Fist and Northern Leg?

At Tai Chi Wuji, we see "Southern Fist, Northern Leg" not as a strict choice, but as a valuable spectrum of knowledge. Our training philosophy respects the deep roots of traditional styles while embracing the modern, adaptive spirit. We believe in teaching the fundamental principles of both—such as rooted power from the south and agile movement from the north—to help our students develop a well-rounded, effective, and personal understanding of Chinese martial arts.