You’ve heard the phrase “master of the 18 arms,” but what does it actually mean? Forget scrolling through endless, dry historical texts. Here’s the straight answer:

The 18 Arms of Wushu are the core classical weapons of Chinese martial arts. Think of them as the original toolkit for a warrior, each designed for a specific purpose on the battlefield. But today, they're less about combat and more about building an unstoppable body and mind. They are the ultimate key to understanding the depth of Kung Fu and Tai Chi.

In a nutshell: If you want to develop power, coordination, and a profound connection to Chinese martial culture, learning these weapons isn't an option—it's essential.

So, let's cut through the noise and get to the good stuff.

Where Did the 18 Arms of Wushu Come From? (A Quick History)

This isn't just ancient history; it's a story of adaptation. The "18 Arms" concept didn't pop up overnight. It evolved over centuries, starting around the Warring States period.

Here’s the timeline that shaped it all:

- Warring States Period (c. 475–221 BC): The idea was born. Military strategists like Sun Bin and Wu Qi supposedly conceptualized it. Why? To systematize soldier training.

- Han Dynasty (202 BC–220 AD): Big tech upgrade. Iron replaced bronze, making weapons stronger and deadlier. This was a game-changer.

- Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD): The shift begins. Some weapons started their transition from battlefield killers to ceremonial status symbols.

- Yuan & Ming Dynasties (1271–1644 AD): The list solidifies. This is when the term "18 Arms" appears in operas and military texts. The classic list we often use today was basically set.

- Qing Dynasty to Modern Day: The final pivot to performance and health. With guns making most of these weapons obsolete, they found a new life in traditional martial arts, opera, and as tools for physical cultivation.

The 18 Arms aren't a static list.

They're a living record of Chinese military and cultural history. They adapted to survive.

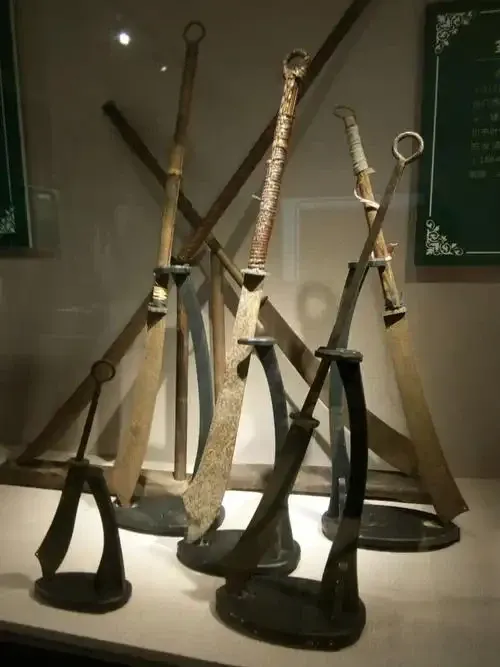

The Complete List: What Are the 18 Weapons?

Here’s the definitive list of the classic 18 Arms, with a plain-English breakdown of what makes each one unique:

| Weapon Name (Chinese) | Key Characteristics & Use |

|---|---|

| 1. 刀 (Dāo) - Broadsword | The fierce slasher. Single-edged, curved blade designed for powerful chopping and cutting. |

| 2. 枪 (Qiāng) - Spear | The "King of Weapons." A long-range piercing tool that teaches precision and whole-body power. |

| 3. 剑 (Jiàn) - Straight Sword | The "Gentleman of Weapons." A double-edged, straight blade for thrusting and elegant, precise cuts. |

| 4. 戟 (Jǐ) - Halberd | A battlefield multitool. Combines a spear point with an axe head for piercing, hooking, and chopping. |

| 5. 斧 (Fǔ) - Axe | Pure, brute-force power. A heavy blade on a handle for devastating chops. |

| 6. 钺 (Yuè) - Battle-Axe | A larger, more ceremonial version of the axe, often symbolizing authority. |

| 7. 钩 (Gōu) - Hook Sword | Uniquely Chinese. Features a sharp hook for disarming opponents and a blade for striking. |

| 8. 叉 (Chā) - Fork | A simple but effective multi-tined weapon for thrusting and trapping enemy weapons. |

| 9. 鞭 (Biān) - Iron Whip | A heavy, rigid bar made of linked sections. Designed to smash through armor. |

| 10. 锏 (Jiǎn) - Mace | Similar to the whip but often with a ridges. A crushing weapon without a sharp edge. |

| 11. 锤 (Chuí) - Hammer | The ultimate blunt-force instrument. Often used in pairs to deliver overwhelming power. |

| 12. 抓 (Zhuǎ) - Claw | A bizarre but effective weapon. A metal claw on a stick, used to grab and tear. |

| 13. 镋 (Tǎng) - Trident-Halberd | Like a fork on steroids. A long spear with two crescent-shaped blades on the sides. |

| 14. 棍 (Gùn) - Staff | The "Grandfather of all Weapons." A simple wooden rod that teaches fundamental power and control. |

| 15. 槊 (Shuò) - Long Lance | A heavy cavalry spear. Long, powerful, and designed for use on horseback. |

| 16. 棒 (Bàng) - Club | A shorter, thicker, and more brutal version of the staff. All about impact. |

| 17. 拐 (Guǎi) - Tonfa | The classic side-handle baton. Excellent for blocking, striking, and joint locks. |

| 18. 流星 (Liúxīng) - Meteor Hammer | The ultimate flexible weapon. A weight on a long rope, requiring incredible skill to control. |

How Are the 18 Arms Classified? (Making Sense of the Chaos)

With 18 different weapons, it can feel overwhelming. How do you make sense of it all? Think of it like organizing a toolbox.

You don't just throw everything in a drawer. You group them by what they do. Chinese masters did the same thing.

By Length: The "Nine Long and Nine Short" System

This is a classic, intuitive way to split them up.

The Nine Long (for reach and power):

- Spear, Halberd, Staff, Battle-Axe, Fork, Trident, Hook, Lance, and Spade.

- Use Case: Keeping your enemy at a distance, controlling the battlefield, and generating immense power through leverage.

The Nine Short (for agility and close-quarters):

- Broadsword, Straight Sword, Tonfa, Axe, Whip, Mace, Hammer, Club, and Pestle.

- Use Case: Quick draws, tight spaces, and powerful, compact movements.

By "Hardness": Rigid vs. Flexible

This is where it gets really interesting for a modern practitioner.

Hard Weapons (like the Staff, Spear, and Broadsword):

- What they teach you: Power generation, structure, and precision. You learn to channel force directly from your body through a rigid object.

- Why it matters for Tai Chi: It makes your movements more rooted and powerful. You can't be sloppy with a heavy spear—it forces your structure to be correct.

Soft Weapons (like the Meteor Hammer and Rope Dart):

- What they teach you: Unbelievable coordination, timing, and spatial awareness. You're controlling momentum, not just muscle.

- Why it matters for Tai Chi: This is the ultimate expression of "sticking and yielding." You learn to redirect energy in its purest form. It’s a moving meditation on flow.

The Big Insight: Training with a hard weapon shows you how to be solid like a mountain. Training with a soft weapon shows you how to be flowing like water. A complete martial artist needs to understand both.

Why Should a Modern Martial Artist Bother with These Weapons?

Let's be real. You're not planning to storm a medieval castle. So, why spend hours learning to swing a 7-foot spear or untangle a meteor hammer?

The answer is simple: Weapons are the ultimate teacher.

They aren't just accessories to your empty-hand forms; they are the fastest way to expose your flaws and amplify your power. Think of them as a brutal, honest feedback system for your body.

The Unbeatable Benefits of Weapon Training

- ✔️ They Build Functional Strength. You can't curl a 10-pound dumbbell and call it functional. But try holding a Zhan Zhuang (standing post) stance with a heavy staff extended. You’ll feel your legs, core, and back ignite in a way no gym machine can replicate. This is strength you can use.

- ✔️ They Supercharge Your Coordination. Your body and the weapon must move as one. If your hands are clumsy, the spear wobbles. If your footwork is off, the broadsword feels awkward. Weapons force your nervous system to level up.

- ✔️ They Deepen Your Understanding of Force. Ever hear a Tai Chi master talk about "issuing power" (Fa Jin)? It's an abstract concept until you hold a whip or a staff.

A hard weapon teaches you direct, penetrating force.

A soft weapon teaches you whipping, shocking force.

You don't just think about energy—you feel it, channel it, and project it.

A top-tier instructor once told me: "Your empty-hand form is the shadow. The weapon is the substance. You can fake a punch, but you can't fake the vibration of a well-executed staff strike."

The Tai Chi and Internal Arts Connection

If you practice Tai Chi, this is non-negotiable. The classic weapons—Jian (sword), Dao (saber), and Qiang (spear)—are considered extensions of the core principles.

- Tai Chi Jian (Sword): This is where "softness overcomes hardness" comes to life. The flexible, double-edged Jian requires finesse, not brute force. It’s a moving meditation on precision, timing, and yielding. There's no "muscling" a perfect Jian technique.

- Tai Chi Dao (Saber): This teaches you how to express controlled, explosive power. The saber form is more vigorous, training your ability to generate power from the waist and deliver it with intent.

- Tai Chi Qiang (Spear): The spear is all about internal connection. The power doesn't come from your arms; it comes from your back and your root, transmitted through a straight line to the tip. It’s the purest expression of whole-body force.

Which of the 18 Arms Should You Learn First?

Don't try to learn all 18 at once. That's a surefire path to frustration. You need a solid foundation. Here’s a logical, battle-tested path to get you started.

Step 1: The Humble Staff (Gun) - Your Foundation

The staff is the great equalizer. It's the first weapon for a reason.

- Why? It's simple, relatively safe, and unforgiving. It teaches you the most important concepts: leverage, distance management, and full-body coordination. Every mistake in your structure is magnified.

- Your Goal: Learn to make the staff feel like an extension of your spine, not a separate piece of wood.

Step 2: Choose Your Path - The Saber (Dao) or Spear (Qiang)

Once the staff feels natural, you have a choice.

- Choose the Broadsword (Dao) if: You love powerful, committed movements. It's direct, fierce, and great for building leg strength and explosive waist rotation.

- Choose the Spear (Qiang) if: You are fascinated by precision and internal connection. It demands a calm focus and teaches you to project energy to a single, tiny point.

Step 3: The Straight Sword (Jian) - The Refinement

The Jian is often called the "scholar's weapon" for a reason. It's advanced.

- Don't start here. Its light weight and double-edged blade require exquisite control. Without the foundation of the staff and saber/spear, your Jian form will look limp and unconvincing. You earn the right to train the Jian.

A Quick Warning: The flashy stuff like the Meteor Hammer or Hook Swords are graduate-level studies. They look cool on Instagram, but without a rock-solid base, you'll spend more time untangling knots and bandaging yourself than actually training.

How to Actually Start Training (Without Getting Hurt)

This isn't a DIY project from YouTube. Seriously. Getting a 6-foot staff spinning the wrong way can take out a window (or a friend).

Here’s your safe-start checklist:

- ✔️ Find a Qualified Instructor. This is non-negotiable. Look for a school or teacher that has a clear weapon curriculum within their system (e.g., Tai Chi, Shaolin Kung Fu, Choy Li Fut).

- ✔️Start with a Wooden Trainer. Do not buy a sharp, metal sword. A simple wooden Jian or Dao is cheap, safe, and perfect for learning the basics.

- ✔️ Master the "Basics" (Ji Ben Gong) First. Your teacher will make you practice the same thrusts, cuts, and stances for what feels like forever. This is the most important part. Be patient. Precision before power.

- ✔️ Practice in a CLEAR, OPEN SPACE. Indoors, make sure you're at least a full weapon's length (in all directions!) from any furniture, lights, or beloved possessions.

The 18 Arms of Wushu are a lifetime journey. But every journey starts with a single, well-executed step.

Beyond the Battlefield: The Deeper Meaning of the 18 Arms

Let's be clear: the 18 Arms are not a random collection of antique metal. They are a physical library of Chinese philosophy and culture. When you learn these weapons, you're not just learning to fight; you're learning to think.

Think of it this way: each weapon is a different dialect in the language of martial arts. The staff speaks in simple, profound truths. The straight sword communicates with poetic elegance. The meteor hammer talks in flowing, unpredictable verses. To be fluent in Kung Fu or Tai Chi, you need to understand more than one dialect.

This is where the magic happens: The self-discipline you learn from the strict form of the spear translates directly into the focus you need at work or in your personal life. The adaptability you develop from switching between a heavy saber and a light sword? That’s a mindset you can use to tackle any of life’s unpredictable challenges.

From Ancient Warriors to Movie Stars

How did these ancient weapons avoid the scrapheap of history? Storytellers. Chinese opera and, later, Hong Kong cinema became the guardians of this knowledge. The breathtaking fights you see in movies by directors like Zhang Yimou or starring legends like Jet Li are direct descendants of this tradition.

The weapons became characters themselves, each with its own personality and story. This kept the culture alive and burning bright in the public imagination, ensuring that a new generation would always be curious enough to pick up a staff and learn.

Common Myths & Mistakes (What Most Beginners Get Wrong)

Before you run off to buy a sword online, let's clear the air on a few things. I've seen these misconceptions trip up so many eager students.

Myth #1: "I need to buy the coolest, sharpest replica I can find."

The Reality: This is a terrible and dangerous idea. A sharp blade is for display, not for learning. Start with a well-balanced, blunt wooden or synthetic trainer. Your focus should be on form and control, not on pretending to be a movie hero.

Myth #2: "Weapons training is only for advanced students."

The Reality: The opposite is true! The staff and the spear are foundational tools. They are often taught to beginners to build the core strength and body mechanics that make empty-hand techniques more powerful. You don't "earn" a weapon after years of practice; you use the weapon to become a better martial artist, faster.

Myth #3: "I can learn this properly from YouTube."

The Reality: You can learn the sequence of a form from a video. But you cannot learn the essence—the internal power, the subtle angle corrections, the feeling of energy transmission. Without a teacher to correct you, you will ingrain bad habits that are extremely difficult to unlearn. A video can't see your mistakes.

Your Next Step: How to Begin Your Journey

The history is fascinating, the philosophy is deep, but none of it matters without action. So, what's your move?

If you're serious about this, here is your mission:

- Get Curious, Not Just Furious. Don't just think about which weapon looks the coolest. Ask yourself: What do I need? Do I need to build a stronger foundation (Staff)? Do I need to learn to generate power (Saber)? Or do I need to refine my precision and calm (Straight Sword)?

- Find Your Guide. Search for "Tai Chi weapons class near me," "traditional Kung Fu school," or "Wushu training." Look at the school's website—do they show instructors practicing with weapons? Send an email. A good teacher will be happy to answer your questions and will emphasize safety and basics.

- Embrace the Grind. Your first few months will not look like a Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon scene. It will be repetitive. It will be humbling. Your shoulders will ache from holding a basic spear posture. This is the real work. This is where you build the skill that lasts a lifetime.

Conclusion: The Weapon is a Mirror

The 18 Arms of Wushu are more than a list. They are a challenge, a history lesson, and a tool for self-mastery.

A weapon doesn't lie. It shows you exactly where your power leaks, where your focus wavers, and where your structure is weak. In that sense, the weapon is a mirror. It reflects the practitioner you are today and shows you the path to the practitioner you can become.

The journey through this ancient arsenal is a lifelong pursuit. But every master, every legend, and every quiet practitioner in a park somewhere started exactly where you are now: curious, and ready to take the first step.

So, what will you see when you look into the mirror?

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the most important of the 18 Arms?

While all are important, the Spear (Qiang) is traditionally called the "King of Long Weapons" for its versatility, and the Straight Sword (Jian) is the "Gentleman of Weapons" for its refinement. However, for building a solid foundation, the Staff (Gun) is arguably the most important for beginners.

Are the 18 Arms of Wushu still used for combat today?

No, their practical military application ended with the advent of firearms. Today, they are practiced for self-cultivation, physical fitness, and the preservation of cultural heritage within martial arts systems. They are also a core component of modern Wushu (performance martial arts) competitions.

Which of the 18 Arms is the easiest for a beginner to learn?

The Staff (Gun) is universally the best starting point. It's inexpensive, safe to practice with, and teaches the fundamental body mechanics that apply to all other weapons. It builds strength, coordination, and spatial awareness without the complexity of a blade.

Which is the hardest weapon to master?

The Meteor Hammer (Liuxing) is notoriously difficult due to its flexible nature. It requires an extremely high level of timing, spatial awareness, and coordination to use effectively without injuring oneself. The Hook Swords (Gou) are also very complex due to their unique shape and techniques.

How are the 18 Arms related to Tai Chi?

Tai Chi integrates weapons as moving meditation to deepen internal principles. The Tai Chi Straight Sword (Jian) cultivates lightness, precision, and mental calm. The Tai Chi Broadsword (Dao) develops explosive power from the waist. The Tai Chi Spear (Qiang) trains whole-body connection and internal force (Jin).

Did the list of 18 Arms ever change?

Yes, the specific list has varied throughout history and by region. The version we use today is the most common one that became standardized in the Ming and Qing dynasties, particularly through opera and martial arts societies. Earlier lists sometimes included bows, crossbows, or shields.

Can I learn these weapons from online videos?

You can learn the basic shapes and sequences of a form online. However, to understand the combat applications, internal power generation, and subtle body mechanics, a qualified instructor is essential. A teacher provides real-time correction that videos cannot, preventing you from ingraining bad habits.

What's the difference between a Dao and a Jian?

This is a fundamental distinction: Dao (Broadsword): Single-edged, curved. Used primarily for slashing and chopping. It's a more aggressive, power-oriented weapon. Jian (Straight Sword): Double-edged, straight. Used for thrusting, slicing, and precise cuts. It's a more refined, technique-oriented weapon.